I have decided it was time for me to gather my Master’s thesis notes and publish a blog post about it.

Introduction to Codon Usage Optimization Problem

All living organisms are made up of cells, which can group together to form tissues and organs. From biology, we know that all genetic material is encoded in DNA. Regions on DNA that are transcribed into RNA are called genes. These can be synthesized by the cell into proteins, which are long chains of amino acids. Proteins perform most of the functions in a cell, for example, converting glucose into energy or facilitating the transport of molecules across membranes. To compare, in a human cell, we have two copies of DNA, more than 20,000 genes, and over 100,000 different proteins. Proteins can also perform functions outside of cells. Proteins from organisms are used in the production of medicines, for example, to produce synthetic insulin, in the food industry, or in studying protein properties in laboratories.

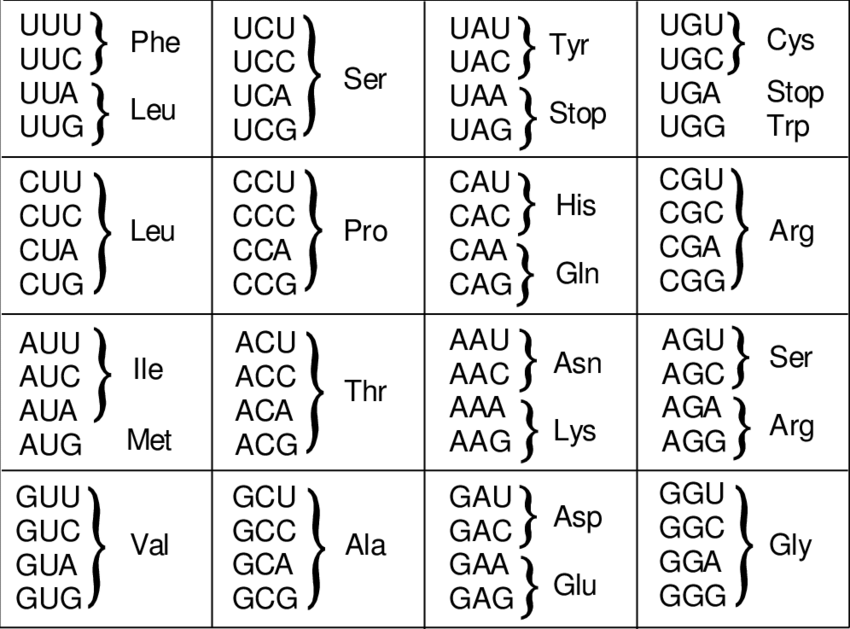

Two steps are necessary to produce proteins. First, we take the genetic sequence for the desired protein from the host organism. Then, we insert this sequence into an organism that will produce the protein, such as yeast or Escherichia coli. Proteins are encoded in DNA as sequences of codons, where each codon represents one amino acid. Codons are sequences of three nucleotides. With the four nucleobases, represented by the letters A, C, G, and U, we can form 4^3 or 64 different combinations. Some codons specify the same amino acid, or they serve as signals to start or stop transcription, known as START or STOP codons. For example, the amino acid alanine is encoded by four different codons: GCU, GCC, GCA, and GCG, as shown in the figure. These different codons encoding the same amino acid are called synonymous codons.

Although all organisms use the same codons to encode amino acids, the frequency of codon usage varies between organisms. In the table, we see that human genes use the GCG codon in 11% of cases, while E. coli uses it in one-third of cases. Therefore, it is crucial to adapt the codon sequence according to the relative codon usage of the host organism before insertion.

| Alanine | Relative frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Codon | Human | E. Coli |

| GCU | 0.26 | 0.18 |

| GCC | 0.40 | 0.26 |

| GCA | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| GCG | 0.11 | 0.33 |

Goals

The aim of this Master’s thesis was to design an algorithm capable of adjusting codon usage for protein expression in the host organism. Algorithms for optimizing codon usage based on relative usage already exist and have been in use for several years.

However, in designing our algorithm, we considered an additional property of protein synthesis influenced by codons – the translation speed of different codons. Using a statistical model, we can predict the translation time for any codon sequence. Based on the protein structure, we can predict translation time using a model developed by my co-supervisor, Martin Špendl, which employs deep neural networks. Our goal is to generate a codon sequence whose translation time closely matches the prediction.

Since we wanted the algorithm to be useful and accessible for biologists, we set the following objectives.

- Implementation of the TASEP algorithm for protein translation modeling

- Design and implementation of algorithms for codon usage optimization

- Web application for codon usage optimization – The user can adjust the translation time – Minimizing the execution time of algorithms – Asynchronous execution of algorithms on distributed servers

- Algorithm analysis

- Evaluation of the web application

In this Master’s thesis, we used the organism Escherichia coli (E. coli). However, the methods and algorithms are also suitable for other host organisms.

Codon Usage Optimzation

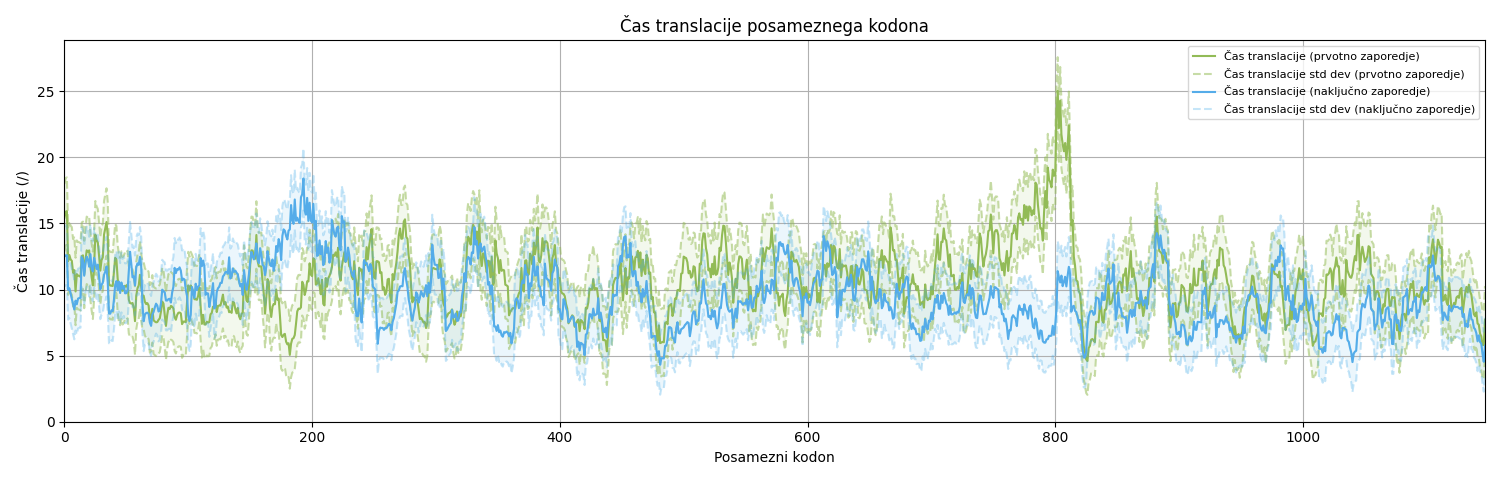

We designed the codon usage optimization based on the amino acid sequence and target translation time in the following steps. First, we convert the amino acid sequence into a nucleotide sequence. Then, we replace synonymous codons in the sequence and attempt to create a better candidate. Based on this new sequence, we calculate the translation time using the TASEP algorithm. We compare the result with the desired or predicted translation time, and we accept the candidate only if the new sequence brings the translation time closer to the predicted time. We then iterate until we achieve sufficient improvement.

Calculating translation time is a computationally intensive operation, so we aim to generate candidates for better sequences as efficiently as possible, in the fewest number of iterations.

For selecting better candidates, we developed two algorithms, one based on a random walk and the other on the RTA* algorithm.

Protein Translation Modelling

To model protein translation, we implemented the TASEP algorithm. TASEP is a model that simulates the movement of particles along a chain. The particles move only in one direction, one step forward, and cannot overtake each other. Only one particle can occupy a position at a time. Ribosomes move along the mRNA according to the same rules (randomly from codon to codon, without overtaking, in a straight line). The input to the algorithm is a protein encoded as a sequence of codons. The output of the function is a list of translation times for each (input) codon, which approximates the actual translation time of the protein.

Random Walk Algorithm

In the random walk algorithm, we iterate until we reach the desired number of iterations. We start with the given codon sequence, and in each iteration, we replace one or more codons. After the codon replacement, we use the TASEP algorithm to calculate the new translation time. If the difference between the translation time and the reference translation time is smaller for the new sequence, we accept the sequence; otherwise, we reject it. The difference is defined as the sum of the squared differences between the reference translation time. The output of the function is the new codon sequence and the translation time.

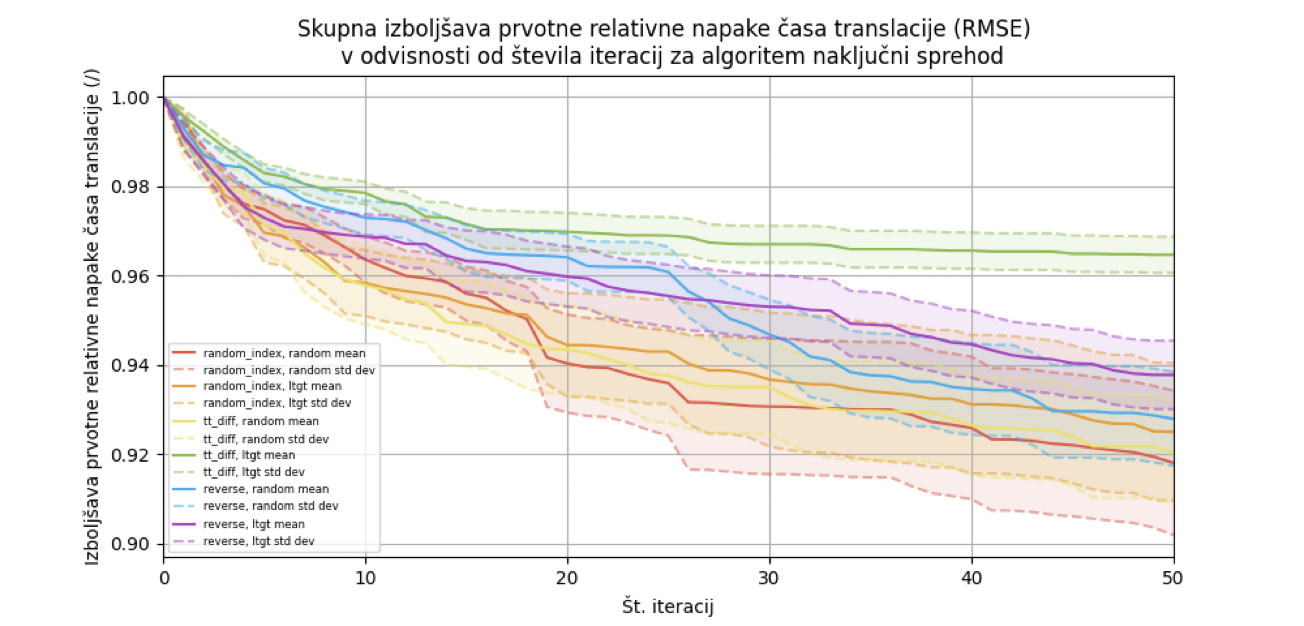

In the random walk, we can implement the replacement of one or more codons in different ways. The process is divided into two steps: selecting the codon replacement site and selecting the synonymous codon. First, we choose one or more positions where we will replace the codon. Then, for each chosen position, we select a synonymous codon. For selecting the replacement site for one or more codons, we used three different approaches: random site, largest deviation from translation time, and reverse mode. For selecting the synonymous codon, we used two different approaches. We can choose a random synonymous codon or select the one that optimizes the difference between the translation time and the reference value. After each selection of a synonymous codon, the TASEP algorithm must be rerun to get a new translation time approximation.

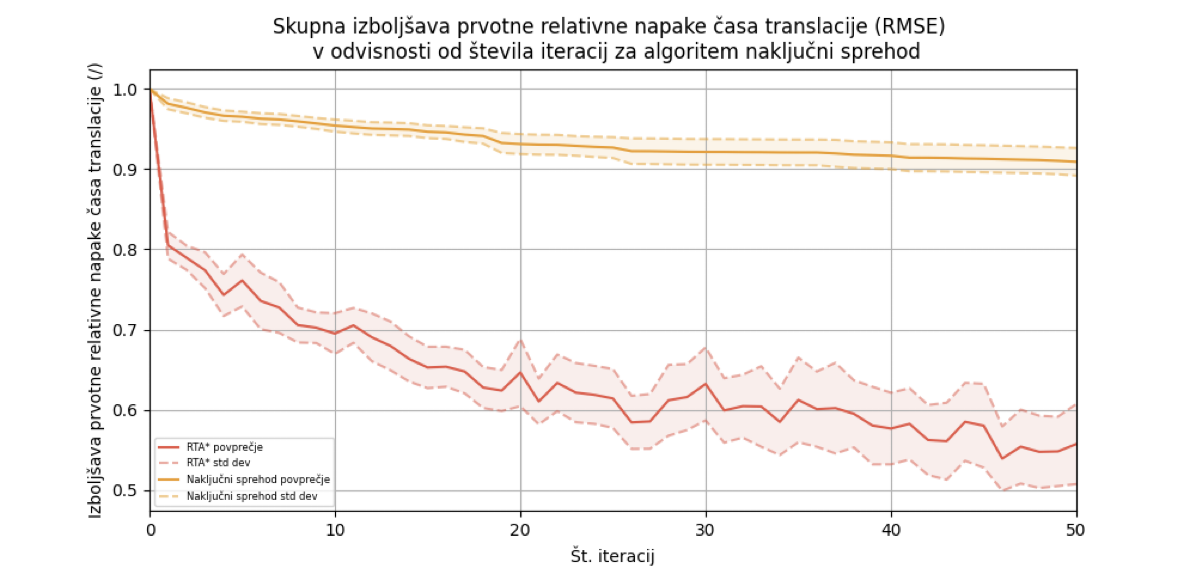

We ran the random walk algorithm for each of the 12 input combinations on 36 test cases and calculated the average improvement in the initial relative translation time error concerning the number of iterations. The error decreased to 91% after 50 iterations, with a standard deviation of 1.6%.

RTA* Algorithm

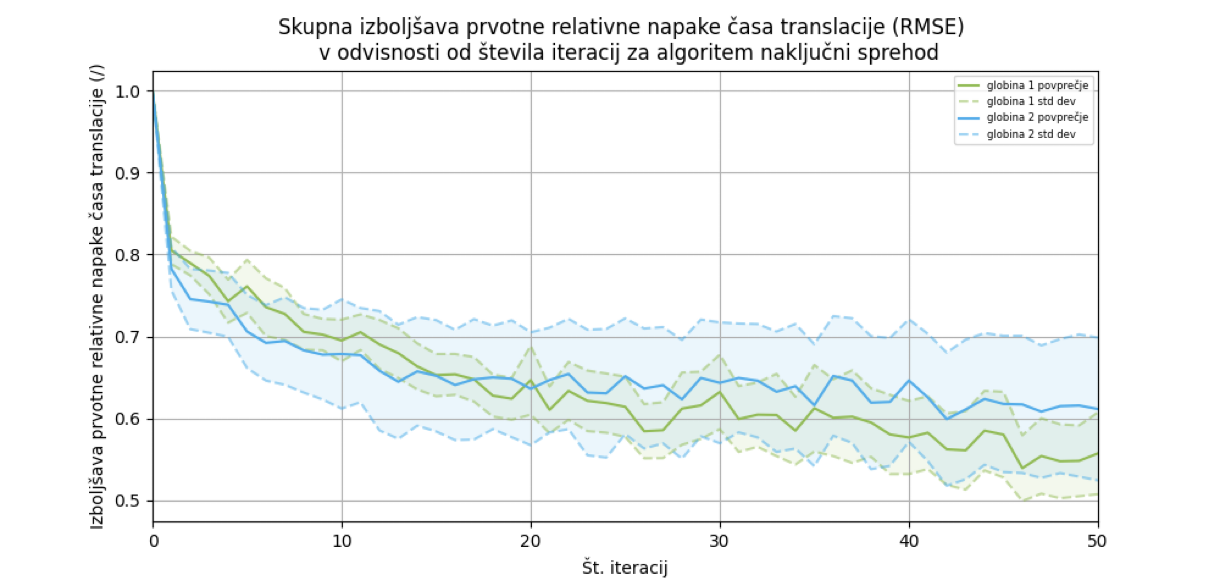

The idea behind the RTA* (Real-Time A*) algorithm originates from the A* algorithm, which is adapted to solve more complex problems where a real-time solution is required. In the classic A* algorithm, the agent is given the information about the target it needs to reach. The agent first creates a detailed, optimal action plan and only then begins to execute it. However, this approach is not suitable for more demanding problems because the planning phase can take too long, during which the agent takes no action.

RTA* can solve complex problems in real-time, though the solution may be suboptimal.

The heuristic function we used to guide the algorithm operates based on translation times. The heuristic receives the current translation times for each codon, the old and new codon sequences, and adjusts the translation time for the entire sequence based on the elongation time.

We ran the RTA* algorithm with two different parameters: depth 1 and depth 2, where the best results were achieved with depth 1. At depth 1, the average relative improvement in error dropped to 55.71% ± 4.99%. The RTA* algorithm achieves the greatest improvement within the first few iterations.

Algorithm Comparison

Finally, we compared both algorithms. The RTA* algorithm achieved the highest error improvement, so we integrated it into the web application.

Web Application

Before developing the web application, we gathered user requirements and refined them over several iterations. The user of the application is a biologist who wants to optimize codon usage in proteins.

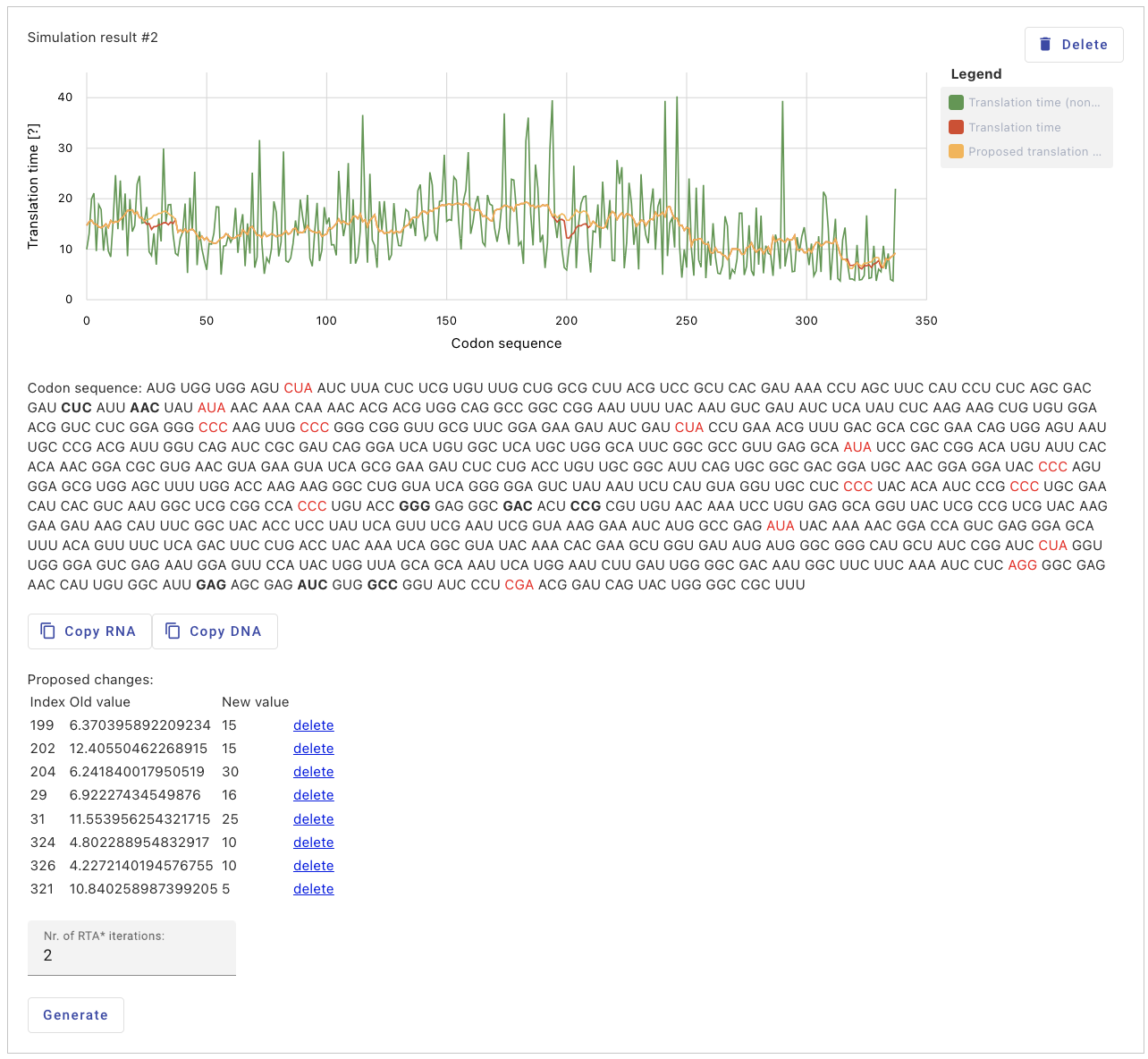

In the web application, the user inputs the protein as an amino acid sequence and uploads the protein structure in PDB format (from the DSSP database). The application generates an initial random codon sequence and the corresponding protein translation time using the TASEP algorithm, which serves as the starting point for further optimization. For the given codon sequence, the user obtains the translation time from the ANN model and generates a new codon sequence based on the obtained translation time using the RTA* algorithm. The user can manually adjust the translation time at specific positions and obtain a new codon sequence. In the current sequence, codons with altered translation times are visually distinguished from others. Rare codons are also visually highlighted. The user can iterate this process multiple times, generating new, more optimal codon sequences. In case of an error or an undesired result, the user can return to the previous step and continue from the previous state.

Web Application Architecture

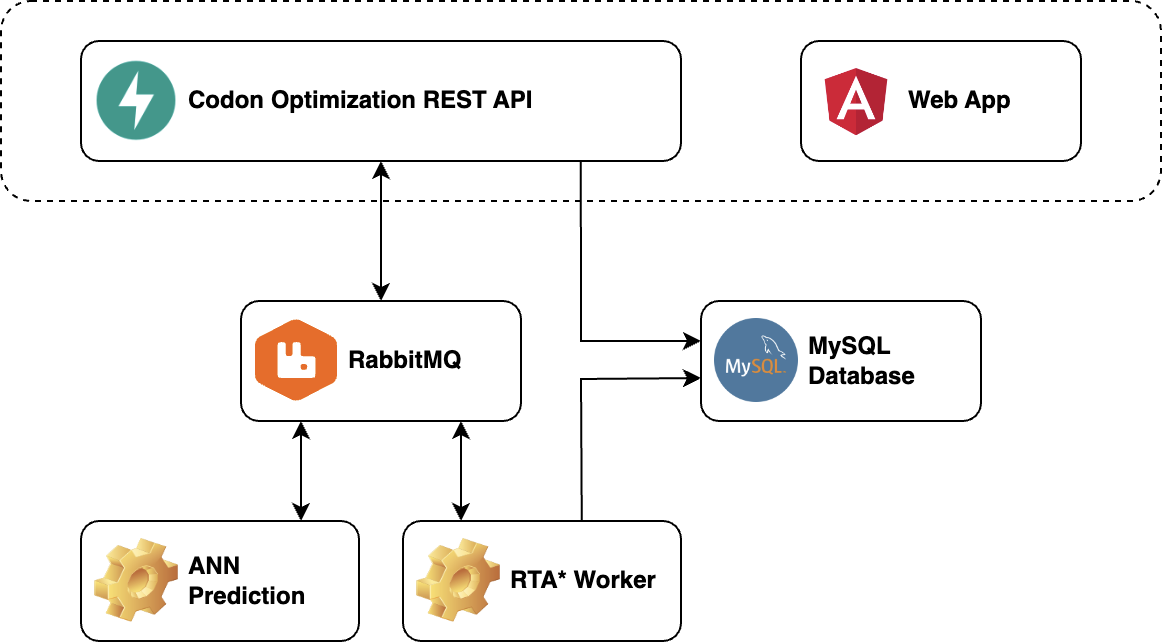

The web application consists of a front-end and back-end. The front-end includes a user interface for codon optimization, built with the Angular framework in TypeScript, allowing interactive codon usage optimization. The back-end is made up of three microservices, written in Python: a REST interface for codon optimization, a translation time prediction model, and an executor for the RTA* algorithm. These microservices communicate by exchanging messages through the RabbitMQ message broker, with data stored in a MySQL database.

We packaged the developed components into Docker images. All four components, along with the database and RabbitMQ message broker, run in Docker containers using Docker Compose.

Web Application Evaluation

To monitor the user experience of the web application, we conducted a workshop. We introduced the participants to the concept of the codon optimization algorithm, demonstrated the use of the web application, and finally, participants completed a survey. The workshop involved 23 target users of the web application, consisting of biochemists and molecular biologists looking to optimize codon usage. The survey contained 10 questions, and the key findings are as follows: 91% of users responded that the user interface meets all their requirements for optimization. 69% of respondents indicated that the algorithm execution speed is sufficiently fast. All users stated that they would use the algorithm or application in their work. Based on the results, the users’ feedback met our expectations.

Summary

To summarize, we designed an algorithm in this thesis that selects the most appropriate codon sequence based on the amino acid sequence and target translation speed. The method represents a significant advancement in research. The average relative improvement in translation time error was reduced to 55%, with a standard deviation of 4.99%. The algorithm, together with the translation speed prediction model, has been implemented in a web application, which encompasses the entire process of preparing sequences for codon optimization based on the protein structure. As mentioned earlier, we presented this application to the target users, and it was well received.

We propose the following ideas for future research: In cases where codon optimization is needed in the shortest possible time, it would make sense to perform only a few iterations of the algorithm. Instead of running the algorithm with a larger number of iterations, it may be worth exploring a method where, instead of generating a single sequence, we generate N random sequences and attempt to improve all sequences within a few iterations of a random walk or RTA*, which can run in parallel.

References

- My Master’s thesis: Web Application for Codon Usage Optimization (Repository of the University of Ljubljana)